About

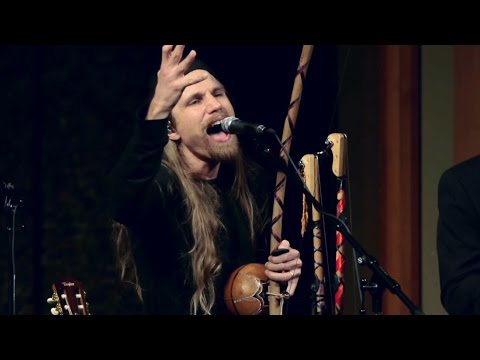

GUY MENDILOW ENSEMBLE

"An international tour de force” (Bethlehem Morning Call) from the Middle East, South and North America, the Guy Mendilow Ensemble operates on the notion that incredible stories and emotionally sweeping experiences can do far more than just entertain. They can spark resonance, fascination and motivation to care beyond our day-to-day. ...

Contact

Game of Tones: Guy Mendilow Ensemble Revives the Fantastic World of Ladino Song with Global Grace in Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom

A queen who runs away with her slave, joining her fate to her beloved servant’s. Brides who abandon their weddings and join a shipful of sailors. Men who go courting, only to get taunted or tossed down a well.

These wild rides and fantastic yarns spring from Ladino tradition, from songs and stories carried by Sephardic Jews as they moved from Spain and settled along the Mediterranean’s northern coast to Greece and Turkey. In multicultural metropolises like Sarajevo, in picturesque island towns like Rhodes, Jewish culture-bearers recounted the romantic escapades and derring do of a cast of characters worthy of a cutthroat fantasy novel.

Multi-instrumentalist, singer, and skilled arranger Guy Mendilow and his four musical collaborators leap into this world in Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom. The intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Hebrew, and Greek. By digging deep into Sephardic scholarship and revitalizing the sound recorded on gritty field recordings, Mendilow and company bring tales to life, intertwining voices, percussion, and soulful playing to render these songs in all their color, drama, and heart.

“If you like Game of Thrones, these stories are for you,” suggests Mendilow with a smile. “The tales are amazing. The melodies twist and turn, like the culture of adaptation Sephardic musicians embraced. Much of it is modal music, with elements that run from epic tunes to early 20th-century foxtrots and tangos, and all of it is mesmerizing, in its beauty and intensity.”

Audiences will get to savor this intensity this autumn, as the ensemble tours the U.S. in a series of concerts, residencies, and community performances.

{full story below}

Mendilow grew up in Jerusalem, hearing various renditions of Ladino songs spinning from the family record player, or drifting mysteriously from open windows, as elder women went about their housekeeping. It felt too slick or too rough, and left only a faint impression on the young musician. “The songs were cryptic, the language was mysterious, opaque,” he recalls.

However, once he had mastered Spanish while living in Mexico, and once Mendilow had engaged intensely with Indian classical and other, very different music, he found himself fascinated by Ladino repertoire. The epic stories, tales scholars of Spanish literature prize for encapsulating much medieval material unavailable elsewhere, are coupled with tantalizing, zesty melodies. The combination won Mendilow over.

“As a more mature artist, I was able to listen with more of a musician’s ear, and it was entrancing, those meandering melodies and modes.” The songs’ provenance resonated with Mendilow’s own background. His own family’s generations of migration and relocation echoed the travels and cross-cultural lives of the people who crafted the songs. “The history is fascinating, specific, and yet is a general case study of what happens when people leave one home and settle in another. It’s a similar trajectory to what my family went through, to the adjustments and shifts we each made as individuals in a new cultural context. We each speak with a different accent.”

In tracing this journey, Mendilow was not content to use what he knew from popular recordings, and began to delve into the scholarship and archives about the region that interested him most: the area from Sarajevo, once home to a thriving Jewish population, to the Greek mainland and islands, where Sephardic Jews lived and made striking music. Unlike the more segregated communities to the north and west, Sephardim lived and worked in the midst of non-Jewish neighbors. This delicate fabric was ripped to shreds by World War II.

“We know so much about certain areas, but very little about what happened in areas like Greece, or Bulgaria, or Bosnia,” says Mendilow. “Some of the music we are premiering on this tour was written during the war — one of the pieces was written in Auschwitz about a harrowing cattle-car ride from Salonika — or about the wartime experience. [“O Mis Hermanos”, for example] It’s powerful to meet with elders who have lived through these experiences, who may have heard these songs decades and decades ago from a parent or grandparent, before the Sephardic world in the Eastern Mediterranean was obliterated.”

Despite the grim fate of many communities during the war, Mendilow discovered rough field recordings, such as the collection held at the National Archives of Israel, some of which archivists have since uploaded to the internet. Immersed in the material, he began to explore sounds that might capture the tales and convey them to contemporary, non-Ladino-speaking audiences. He turned to an instrumentarium from around the world, adding Brazilian berimbau and overtone singing, for example, to a mocking treatment of a courtship gone wrong, “Mancevo del dor,” and thumb piano to “Una Noche al Borde de la Mar,” a piece originally from Sofia, Bulgaria.

The overall sound, however, is based on more familiar though equally expressive elements. Singer Sofia Tosello, from Argentina and with a background in tango vocals, weaves her sometimes crystalline, sometimes gritty voice with Mendilow’s pure tenor, creating catchy harmonies and dramatic dialogs. Violinist Chris Baum (who’s worked with everyone from Amanda Palmer to major US orchestras), Palestinian drummer and percussionist Tareq Rantisi, and woodwind player Andy Bergman can be sprightly or lyrical, using a rich palette and creating dense backdrop for the pieces.

“If you went to Salonika in the early 20th century, say, you would never have heard these arrangements,” says Mendilow. “You’d hear women singers a capella, mostly in the home while going about chores, or in community celebrations. There’s lots of research and scholarship behind what we’ve done, but it’s a stylized project to make the stories come alive today.”

To find a way to make the work live and breathe, Mendilow had to set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of making meaningful work. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a spade a spade. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to our concert. It’s not about that; it’s about bringing the stories to life.” That new life is a precious gift to communities scattered by war, but whose tales of wonder continue to inspire and thrill, like all good stories.