About

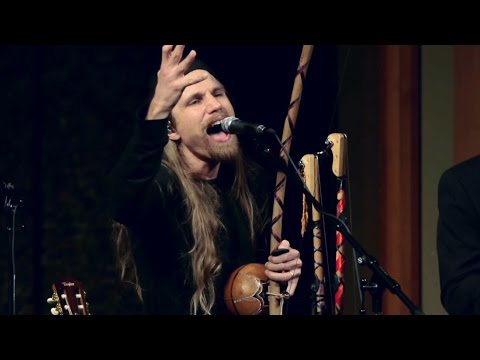

GUY MENDILOW ENSEMBLE

"An international tour de force” (Bethlehem Morning Call) from the Middle East, South and North America, the Guy Mendilow Ensemble operates on the notion that incredible stories and emotionally sweeping experiences can do far more than just entertain. They can spark resonance, fascination and motivation to care beyond our day-to-day. ...

The Guy Mendilow Ensemble tours four shows: The Forgotten Kingdom; Three Sides to Every Story (ft. Philadelphia Girls Choir); Heart of the Holidays — A Global Celebration in Song; and Around the World in Song family concerts. Highly skilled educators, the ensemble specializes in community engagement including tailor-made residencies, choral/string collaborations and a breadth of interactive workshops. The Ensemble is an artist-in-residence with Celebrity Series of Boston's Arts for All since 2014.

In 2017, the National Endowment for the Arts selected the Guy Mendilow Ensemble for its Art Works, a grant for the creation of art that meets the highest standards of excellence, public engagement with diverse and excellent art and the strengthening of communities through the arts.

Alongside touring with the Guy Mendilow Ensemble, members are on the faculty of music schools like the Swarnabhoomi Academy of Music in India and tour/record with the likes of Bobby McFerrin, Yo Yo Ma, Snarky Puppy, the Assad Brothers, Christian McBride, the Video Game Orchestra, Amanda Palmer and Simon Shaheen. Formed in 2004, the Ensemble is based in Boston, MA and New York, NY, USA.

Contact

Current News

- 08/07/201710/06/2017

The Musical Lessons of Lost Worlds: How Guy Mendilow Ensemble Engages Creatively with the Sephardic Past to Inform the Present on The Forgotten Kingdom

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the...

- Jewish Journal, Concert preview, 07/23/2015, Game of Tones: Guy Mendilow Ensemble Revives the Fantastic World of Ladino Song Text

- The Union-Bulletin, Concert preview, 07/30/2015, Tickets for Guy Mendilow performance on sale Friday Text

- Celebrity Series of Boston, Feature story, 08/01/2015, Neighborhood Arts Text

- Culture and Cuisine, Article, 08/19/2015, Our World Interviews-Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom Text

- The Jewish Advocate, Concert preview, 08/21/2015, Guy Mendilow shares his love for Ladino music

- Boston Arts Diary, Concert preview, 08/26/2015, Up, and Coming: Tales From The Forgotten Kingdom The Guy Mendilow Ensemble Text

- Red Bluff Daily News, Concert preview, 09/10/2015, Guy Mendilow Ensemble to kick off series at State Text

- worldbeatcanada.com, Concert listing, 09/17/2015, Vancouver Event Listings: LOOKING AHEAD Text

- Artslandia, Article, 09/28/2015, Evergreen Cultural Centre Text

- Harbour Living, Concert preview, 09/28/2015, Port Theatre Spotlight: Guy Mendilow Ensemble Text

- The Georgia Striaght, Concert listing, 09/30/2015, Guy Mendilow Ensemble Text

- Nanaimo News Bulletin, Concert preview, 10/01/2015, Epic adventure: Guy Mendilow Ensemble to perform songs in a rare language

- Travel Portland, Concert listing, 10/01/2015, Fall jazz and classical music guide Portland’s fall music scene is even more international than usual. Text

- Jewish Federation of Greater Portland, Concert preview, 10/05/2015, Oct 8 2015 Guy Mendilow Ensemble: Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom Performance Text

- Willamette Week, Concert preview, 10/05/2015, Guy Mendilow Ensemble Text

- Oregon ArtsWatch, Concert preview, 10/07/2015, Weekend MusicWatch Text

- Blogfoolk, Album review, 11/12/2015, Guy Mendilow Ensemble: Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom Review Text

- Blogfoolk, Album review, 12/03/2015, Guy Mendilow Ensemble: Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom Review Text

- Boston Event Guide, Listing, 08/18/2016, Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom Text

- Colorado College Bulletin, Event preview, 08/31/2016, Family & Friends Weekend 2016 Text

- Jewish World, Event preview, 09/06/2016, ‘Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom’ to showcase Ladino story/song at Union College Text

- The Daily Gazette, Event preview, 09/08/2016, Duo Dmitri, Mendilow slate local concerts

- Times Union, 09/14/2016, Picks of the week Text

- Valley Journal, Event preview, 09/14/2016, Stories through music Text

- Seven Days, Event preview, 09/14/2016, Welcome Back, Performing Arts Season Text

- Vermont Public Radio, Event preview, 09/22/2016, The October Song About The White Sandy Beach Text

- Burlington Free Press, Event preview, 09/22/2016, Warm up with the Burlington Free Press Fall Arts Preview Text

- Visit Denver, Listing, 09/23/2016, DU Lamont Guest Artists – Guy Mendilow Ensemble, Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom Text

- Missoulian, Listing, 09/30/2016, Out and About: This week in arts and entertainment Text

- Missoulian, Event preview, 09/30/2016, Sanders County concert season opens with Sephardic songs Text

- KPAX, Event preview, 09/30/2016, Upcoming Western Montana events Text

- Missoulian, Event preview, 10/03/2016, Mission Valley Live performances coming to Flathead Text

- Colorado Springs Independent, Event preview, 10/04/2016, Blind, the Thief releasing new EP Text

- Lively Times, Event preview, 10/04/2016, UPCOMING EVENTS AT LINCOLN COUNTY HIGH SCHOOL AUDITORIUM

- Visit Montana, Listing, 10/04/2016, Sunburst Performance Series: Guy Mendilow Ensemble. Text

- Flathead Beacon, Listing, 10/04/2016, The Guy Mendilow Ensemble Text

- Oregon Live, Listing, 10/04/2016, Guy Mendilow Ensemble (External Submission) Text

- Vermont Public Radio, Event preview, 10/05/2016, Oscar Brand And The Chimes Of Freedom Text

- Eugene Weekly, Event preview, 10/06/2016, Groovy, Jazzy October Text

- Sanders County Ledger, 10/06/2016, Judeo-Spanish musical history at the Rex Text

- KLCC, Feature story, 10/07/2016, Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom, with the Guy Mendilow Ensemble Text

- Register Guard, Event preview, 10/11/2016, The forgotten kingdom of the Jews Text

- Burlington Free Press, Event preview, 10/13/2016, Brent's Music Picks: David Bromberg Quintet Text

- Maine Today, Listing, 04/25/2017, Guy Mendilow Ensemble: Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom Text

- Maine Today, Event preview, 05/02/2017, KARLA BONOFF, GUY MENDILOW ENSEMBLE AND CHRISTOPHER CROSS PLAY MAINE ON SUNDAY Text

- The Forecaster, Listing, 05/10/2017, Arts Calendar: May 10-20 Text

- The Portland Press Herald, Event preview, 05/11/2017, Guy Mendilow Ensemble Text

- Maine Public Radio, Listing, 05/14/2017, Tales from the Forgotten Kingdom Performed by the Guy Mendilow Ensemble Text

- Portland, Maine, Listing, 05/14/2017, EVENTS DOWNTOWN Text

- The Jewish Advocate, Article, 09/15/2017, Guy Mendilow Ensemble and the 'Forgotten Kingdom' Text

- Guy Mendilow, Interview, 11/10/2017, A Backstage Tour Of The Forgotten Kingdom (Part 5): Radio Free America Text

- Guy Mendilow, Interview, 11/20/2017, A Backstage Tour Of The Forgotten Kingdom (Part 6): When Stories Collide Text

- Midwest Record, Article, 09/18/2017, GUY MENDILOW ENSEMBLE/Music from the Forgotten Kingdom: Text

- Savannah Morning News, Event preview, 09/28/2017, Get Revived Text

- Wilma, Event preview, 10/01/2017, Calendar Text

- The Daily Times, Feature story, 10/05/2017, Music, narration combine for a journey with the Guy Mendilow Ensemble Text

- WUOT, Interview, 10/05/2017, Guy Mendilow And The Forgotten Kingdom Text

- The Morning Daily Times, Article, 10/05/2017, Music, narration combine for a journey with Guy Mendilow Ensemble Text

- The Wellesley News, Event preview, 11/27/2017, GUY MENDILOW ENSEMBLE BRIDGES PAST AND PRESENT THROUGH MUSICAL STORYTELLING Text

- News Sentinel, Article, 10/06/2017, 18 things to do in October in East Tennessee Text

- Connecticut Jewish Ledger, Event preview, 10/11/2017, Guy Mendilow Ensemble presents “The Forgotten Kingdom” Text

- Connecticut Jewish Ledger, Event preview, 10/19/2017, Guy Mendilow Ensemble presents "The Forgotten Kingdom" Text

- The Sheridan Press, Event preview, 10/27/2017, WYO Theater to host "The Forgotten Kingdom" Text

- Jewish Journal , Feature story, 10/05/2017, Remembering a ‘Forgotten Kingdom’ Text

- Knoxville News Sentinel, Event preview, 10/06/2017, Guy Mendilow Ensemble "Tales From A Forgotten Kingdom" Text

- Jewish Journal, Article, 10/12/2017, Remembering a 'Forgotten Kingdom' Text

- Perceptive Travel, Feature story, 11/01/2017, Music, Community, And Travel, From The Balkans To The Celtic Lands Text

- Shepheard Express, Album review, 11/14/2017, Guy Mendilow Ensemble: Music From the Forgotten Kingdom Text

- Jazz Weekly , Album review, 12/04/2017, http://www.jazzweekly.com/2017/12/ringer-of-the-weekguy-mendilow-ensemble-music-from-the-forgotten-kingdom/ Text

- WNYC New Sounds, Article, 09/06/2017, #4019: Cross-Cultural Smorgasbord of World Music Text

- National Endowment for the Arts, Video premiere, 12/13/2017, Guy Mendilow Ensemble — Una Noche Al Borde De La Mar Text

- NEA Art Works Podcast, Feature story, 12/14/2017, Guy Mendilow Text

- + Show More

News

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

Voci Angelica Trio (opening) November 30, 2017 at 7:30 PM

Voci Angelica Trio is an international band with members hailing from three continents. Listeners describe the music as "a haute folk sound that mesmerizes and enthralls," where each note "sears itself into a goosebump on your arm."

Straddling the genres of world folk and classical music, the trio creates an ambitious blend of cultures, reinvigorating traditional songs for contemporary audiences. Vocal harmonies elegantly intertwine with lush cello lines and percussion to create a musical fusion that transcends political and geographic borders.

The trio's self-titled EP and second album, "Taking Flight: Live from Japan," both invite listeners to journey through unfamiliar musical landscapes. As Voci continues to unearth musical gems, its musicians have become more attentive to the current situations in the diverse countries they explore. Live performances are a celebration of the group's cultural wayfaring, showcasing the differences and similarities of our shared humanity. In 2017, the trio joined the roster of the Boston Celebrity Series Neighborhood Arts Program which presents free concerts for local communities. In 2013, the trio won an Iguana Music Fund grant from Club Passim to purchase a sound system for their school educational program with Young Audiences of Massachusetts. Voci Angelica's mission has also led to the USA's East Coast, Midwest and Southern regions; Canada; Japan; and South Korea.

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.

Composer and artist Guy Mendilow has followed this path to the past, weaving together vignettes, glimpses, and fragmented stories from and of Sephardic communities around the Mediterranean and Balkans. Many of these communities have been wiped off the map, even their language nearly forgotten. But the characters who sprang from them feel fresh and present, and to Mendilow, their adventures and trials suggested a Sephardic epic of sorts, complete with powerful music and universally resonant emotions and messages.

Rethinking the role of musical aesthetics and spoken word in re-creating these impressions, Mendilow and his Ensemble has recorded The Forgotten Kingdom (release: October 6, 2017). The album has two versions, one with just the music from the show, one reflecting the interwoven stories, complete with spoken interludes. Its vignettes propel listeners from old world and into new, from the mythical (“La Sirena/The Siren”), the actual (“La Vuelta del Marido/The Husband’s Return”) and concluding with the harrowing symbol of the trains to Auschwitz (“De Saloniki a Auschwitz”) that bring this older age to a definite, violent end.

“What has haunted me as I’ve created this production is how it gives us a glimpse into the end of an era, the destruction of an older world,” says Mendilow. “I wanted to explore what it was like to see the breakdown of empires, the glimmers of hope that then evaporate. What is it like to be caught on the wrong side, in that kind of nightmare? What is like to witness your world ending? How did the moment, which seems so inevitable in our historical hindsight, actually feel to those living it?”

{full story below}

The product of years of performance, research, and revising, The Forgotten Kingdom’s intertwining music and storytelling conjure an imagi-nation lost to war and upheaval, recorded in a language that blends archaic Spanish with Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, and Greek. “As far as I know, The Forgotten Kingdom is America’s first semi-theatrical touring production made of Ladino songs from Balkan and Mediterranean communities destroyed in WWII,” says Mendilow. “It’s an evocative trek through former Ottoman lands, an allegory that ultimately begs some questions about ourselves today, and the ways these stories continue to play out, in a modern guise.” Mendilow and ensemble get the adventure to burst “with artistry, refinement, and excitement." (Hebrew Union College).

To make the work live and breathe, Mendilow learned these women's songs, traditionally sung a cappella in homes and communal celebrations, by listening to gritty field recordings. He then set aside notions of purity or authenticity, in favor of finding emotional connection. As he described his ideas to an established Ladino scholar, York University’s Judith Cohen, she laid it on the line: You either keep strictly to tradition and abide by its ways, or you pursue your own ideas, but without calling it traditional. Mendilow opted for the latter.

“That’s one of the most challenging things about the project, the moment that demanded the most soul searching,” he reflects. “The conclusion I came to was that we needed to call a fig a fig. I don’t want someone to think they’ve heard Ladino music when they’ve come to this show. It’s not about that; it’s about rendering a traditional way of life in bold, relatable colors.”

These stories speak to our age, Mendilow feels, which is why this project absorbed him for so long. “The Ladino story is a case study in resilience, in collaboration across ethnic and religious divides, and in evolving identities due to immigration,” says Mendilow. “And I feel this story begs the question: Are we also straddling an older, familiar world, and a newer one we can hardly imagine, like those in the stories did back then?” Mendilow and his fellow musicians strive to set the scene, to craft lively portraits of the characters, leaving ample space for listeners to invest in the tales, outside of the cultural and historical specifics.

Stories get better with the telling, and The Forgotten Kingdom proves no exception. Mendilow and his Ensemble, whose members play with everyone from Amanda Palmer and Snarky Puppy to Yo Yo Ma and Bobby McFerrin, started developing the live performance of The Forgotten Kingdom several years ago. The group toured the show extensively, gathering responses from audiences who had never heard of Ladino, from elders who spoke it and knew the songs from their Sephardi homes decades ago.

Mendilow felt it was time to take to the studio. The group strived to capture the energy and flow of the performance as much as possible, then dove into the texture and nuance in a way that only studio work can allow. He also expanded the project into multimedia thanks to an artist award from the NEA, tapping Ukrainian sand painters and German shadow artists to create animated versions of songs. (Two of these videos will be released around the same time as the album)

“Our goal is to sweep up audiences in an emotional experience,” says Mendilow. “We hope it’s so powerful that those with no prior knowledge or connection to Ladino will leave caring deeply about the culture and the world it creates for us. The stories are too good to be ignored, and the communities from which they come too important in terms of what they represent—from models of integration and inter-ethnic cooperation to their own rich heritage—to be dismissed.”

The past can feel distant, foreign: its communities erased, its memory buried. Yet we can sometimes access it through the fantastic, through storytelling that resonates with lived experience.